55-57 Chevys: Of Rear Axles, Axle Cars and the Legacy of the Tri-Five Chevy

Known globally for its enthusiastic trashing of Tokyo, Nick and Joanne Iarussi’s enraged, prehistoric reptile Godzilla is skillfully disguised as an altered-wheelbase ’55 Chevy! There is no better way to begin the end of this story!

Story by Jim Hill – Part II

The factory 55-57 rear axle was fine for street driving, but suspect for even mildly modified, street/strip engines. For serious horsepower it was woefully inadequate.

If the car was fitted with big, sticky rear slicks, ring and pinion and/or rear axle failure was inevitable. After swapping in a big-cube, mega-torque engine the next step was to beef-up the rear axle. The 60’s solution for many was a late-50’s, early 60’s Oldsmobile or Pontiac rear axle assembly. These units came in big, heavy passenger cars, and had considerably larger, stronger gears and axles.

A big-block slips right in, although with 55’s a slight firewall “massage” is needed. Big-torque and HP would shred the stock rear axle, dictating an upgrade in strength. Here a Holley 4 barrel, aluminum high-rise intake, 2” headers, alternator, power disc brakes, electric fan and alum radiator say this Tri-Five is ready to fly.

Swapping in a ’59-60 Olds required only the removal of the stock Olds leaf spring mounting pads and welding on new pads moved slightly inboard. Ring and pinion sets for Olds-Pontiac units were available from Zoom Gears from 3.08:1 up to 6.14:1, and later, 6.50:1, for really serious competition. Although the Olds-Pontiac axle housing was 1” wider, the Tri-Five’s generous rear fender wells allowed tires up to 9.25” width. Many 55-57’s were subjected to rear fenderwell “radiusing”, via a power saw or the “smoke wrench”. Clearance for big, wide tires was the goal, even at the cost of aesthetics.

This restored ’57 carries the popular “dual quad”, 283, 270 hp option. It came with “Duntov 097” solid-lifter cam, aluminum manifold plus two Rochester 4-GC carbs. Rare OE air cleaner, intake and carbs are now worth thousands! A properly tuned 270 reportedly made more hp than vaunted 283/283 Fuelie.

Some racers preferred using a Posi-Traction type, limited-slip differential assembly. Others used a steel spool. Some used the “poor man’s spool”, a set of Ansen locking spider gears. Others simply arc-welded the spiders in place.

An added bonus to the rear axle swap was the larger Olds/Pontiac drum brakes, and improved braking after a run. Brake linings were usually upgraded front and rear with semi-metallic linings, which were less prone to fading when hot.

Some opted for the GM ¾-Ton rear axle used in Chevy-GMC trucks. These were truck-tough, but limited ring and pinion offerings and hefty weight kept them from gaining the same acceptance as the Olds-Pontiac axles. Few aftermarket makers offered wheels for the “truck rears”, further hampering their popularity.

Al Maynard’s E/Gas ’57 Bel-Air Sport Coupe successfully used a heavy-duty truck rear axle assembly. The “3/4 Ton” units were strong but heavy. The late Maynard, from Warren, MI, was nationally known as a Chevy authority with a photo-memory of Chevy part numbers and production numbers!

Ferd Napfel’s name was often misspelled “Fred”, but his Maryland based, ’55 F/Gas Chevy was nationally known. Napfel’s 283 Chevy used a 50 lb. flywheel and howling 8,000 rpm rev-up as a Modified Eliminator terror.

By the early 70’s the rear axle of choice became the Dana 60 Series, a major improvement in strength. The increased strength and wide ratio availability of gearing was worth the added weight of the Dana 60. Drivetrain firms such as Strange Engineering and Dave Mack’s Atlantic Coast Engineering (ACE) began offering narrowed Dana 60 units with billet steel axles and an equally stout spool, to transfer power to both rear wheels simultaneously.

Fred Hartman’s “Rapid Rodent” ’55 used a small CID engine with a Tunnel-Ram, 2×4 intake for 13 lbs. per CID, G/MP. The late Hartman was known for building strong small CID engines. His well-traveled ’55 was his test-bed.

By the middle 70’s Ford “9 Inch” units gained ground. The “Ford Nine” offered a drop-in, banjo-style differential. Ratio changes could be made without setting up the ring and pinion inside the housing. Like the Olds-Pontiac, a spare “pumpkin” could be quickly dropped into the Ford 9” housing.

Firms such as Currie Enterprises, Atlantic Coast Engineering and Strange offered complete, narrowed Ford 9” housings, to tuck those slicks inside the fenderwells, to improve aerodynamics by reducing drag. A ready to bolt-in 9” axle could be had after just a phone call, with a spool or limited-slip Locker unit, billet steel axles and even Wilwood rear disc brakes.

This ’55 210 missile sports a pair of huge centrifugal superchargers, a 9″ Ford narrowed rear axle, big tires, tubs and a full cage. Red and white paint is sneaky disguise for the apparent radically fast capabilities of this shoebox!

Where rear axle durability was once a “hold your breath” affair, these rear axle improvements all but eliminated failures and greatly improved reliability for racers in Gas or Modified Production classes.

1955-57 Chevy brakes were another thing. Tri-Fives are magnificent cars, but they were designed with 50’s braking technology. Stock drum brakes were marginal at best. For drag racing the solution became available once front disc brakes began showing up in 70’s salvage yards. Late 60’s A-Body GM cars provided front disc brakes that could be adapted for a major improvement in stopping power. For race applications, non-power assisted master cylinders still delivered greater braking power. On the street, standard 11” GM front discs were excellent, especially with the factory power-assist master cylinder system and front/rear proportioning valve. Today all the 55-57 specialty parts houses carry complete disc brake kits. Junkyard scrounging is unnecessary only if one enjoys a “Salvage Yard Safari”.

Dave Hales built this ’55 for D/Gas. A member of the famed S&S Racing Team, from Arlington, Virginia, Hales ran a 283 Chevy for power. Dave’s bright red ’40 Willys is now a favorite at current nostalgia events.

Pat Hardy drove The Hardy Boys Super Stock/T, stick-shift, ’55 Bel-Air Sport Coupe to many class wins in So-Cal. Plain white exterior hid many S/S tricks and a 265 CID rules-required engine. Hardy brothers built a successful speed parts warehouse business in Ontario, Southern California.

Along with better braking front discs came the elimination of wear prone front ball bearings. These were notorious for their brief lifespan and once worn, caused front end “wobble” that could be unnerving, especially at 100+ mph. 55-57 police cars, taxis and ambulances came OE with front tapered roller wheel bearings. Passenger cars did not. For a few years Timken Bearings offered a replacement roller bearing set, but these were discontinued. Factory disc brake systems grafted into 55-57 front spindles had long lasting, modern tapered roller bearings.

Rear leaf spring wrap-up, that unwelcome reaction to high-torque as applied to the rear tires and uncontrolled rear tire bounce on acceleration could be solved with some sort of traction bar installation. Bolt-on traction bars such as the Lakewood/Jenkins adjustable “Bump Bars” worked well, as did homemade, welded-on traction bars. The term “ladder bars” described ladder-like traction bars. Either solution dampened the violent leaf spring wrap-up and planted the rear tires, for hard launching traction.

Cleveland, Ohio’s Rodriguez Brothers plus Jarosz and Plona ran this NHRA Record holding ’56 D/Gasser. Power came from Chardon, OH Gas and Pro Stock racer Ron Hutter. “Hut’s Dyno Shop”, continues to build engines for both drag racing and NASCAR teams.

This very clean, B&W, ’56 two-door wagon was a low-production build in 1956. The G/SA hauler recalls when Stock Eliminator racing was huge for racers and fans. Note “poor man’s trailer”, tow-bar tabs under front bumper for flat-towing.

Front and rear shock absorbers were also upgraded. Some offered limited adjustability of front-end rise. Many preferred a 90/10 ratio. Some more frugal, bucks-down racers used worn-out, stock 55-57 shocks. These shocks had little resistance to upward motion. That allowed the front end to lift, transferring weight to the rear tires, and then quickly settled for a speedy top-end charge. The basic question of front-end stance also created a difference of opinion.

Many thought the classic stance of a Tri-Five Gasser required the “High & Mighty” look. That usually entailed cutting away the Chevy front double A-Frame, ball-joint suspension and installing a straight axle with dual leaf front springs. This permitted hiking the front end of the vehicle, exactly what one school of thought embraced. This may have spelled “classical gas” to some, but most competitive Tri-Five racers opted for lowering the front end as much as possible. A lowered front end was aerodynamically more efficient. The generous “shoebox” profile made any improvement worthwhile.

Straight axle and w-a-y up front end shouts “Axle Car!” Lots of nostalgia Gasser flavor in this cruiser plus 383 stroker small-block. Bet this one sees zero street time during Minnesota’s long winters and salt-peppered roads.

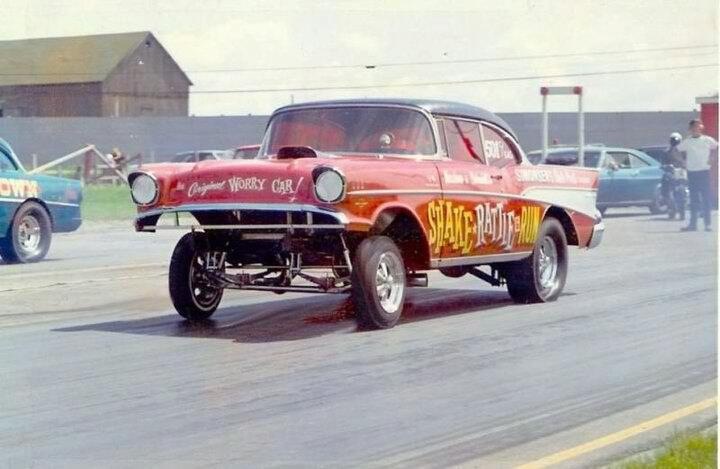

“Shake, Rattle & Run” ’57 Sport Coupe was feared Midwest drag strip staple for decades. Chromed straight axle, long traction bars, Cragar S/S wheels and wheelstands were routine. Definitely an original “Axle Car”!

The “High & Mighty” look actually came about as a means of gaining maximum rear tire traction. Early drag tires had hard rubber compounds, little better than street tires. The high front end stance transferred weight to the rear tires, but also increased wind resistance and often created handling problems. Big, boxy 55-57 Chevys had lots of undercar surface area that created drag and lift at serious speeds. Once tire companies like M&H, Firestone, and Goodyear began producing sticky, rear drag slicks, the need for the stratosphere stance was unnecessary. Giving away 3-4 mph due to undercar wind resistance was unacceptable for those wishing to get to the finish line first.

Of course, logically based scientific fact is often abandoned in the interests of currently popular trends. This may explain the rebirth of the “Classic Gasser” aerial stance. This “look” has made a comeback in Nostalgia Drag Racing circles and the street cruiser set. Today these are called “Axle Cars”, again seen in numbers at these events and cruising.

Tragically, this magnificent ’56 Nomad was stolen and its current situation is unknown. Two-tone paint scheme on ’56 Nomads was sleekly aero in design. Body trim on 55-57’s was not nickel-chrome, but polished stainless steel.

Safety concerns with Tri-Fives increased as speeds grew, especially at the drags. These were addressed by adding a simple roll bar or roll cage system, usually an upright, U-shaped, round tube steel bar with one or two rearward bracing bars mounted behind the driver’s seat. Many early installations were unwisely bolted to the stock floor, or to the frame. Cage systems evolved and improved. The roomy Tri-Five interior allowed plenty of space for whichever design was chosen.

Chevy’s infamous “Black Widow” was factory built for NASCAR racing. Buck Baker wheels the No. 87 Chevy from Nalley Chevrolet. Buck and son Buddy Baker were NASCAR Hall of Fame legends. Note stock, six-lug wheels. In spite of fender lettering, NASCAR outlawed Chevy Fuel Injection but stout 283 engines were still unstoppable with Rochester 4-GC four-barrel carburetors.

The basic 55-57 body shell (except convertibles) was strong and rigid, especially sedans with their roof-supporting pillars. Seat belts were required and later, five-point racing harnesses.

Seating offered several options. Some removed the stock front and rear bench seats, eliminating up to 150 pounds. A popular replacement was light, easily installed bucket seats from a junkyard Volkswagen. Losing the stock bench seat also allowed the use of a straight-stick, Hurst four-speed shifter without the cumbersome “dog leg” design necessary for bench seat use.

Charles Carpenter’s ’55 began its early Pro-Mod career as a fairly stock IHRA Quick-Rod racer. As he went faster the aero challenges posed by the ungainly shoebox forced radical modifications as speeds approached 200 mph.

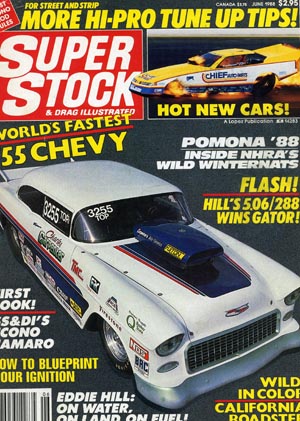

Super Stock Magazine called Charles Carpenter’s ’55 “The Father of Pro-Mod”. Charles’ trusty ’55 helped bring back nostalgic racers with big-inch power, choking nitrous, 200 mph runs and exciting showmanship.

A Sun tach was often mounted atop the steering column or on the dash, as was hanging a gauge panel under the lower edge of the dash. Oil pressure, water temp, amps and voltage instruments kept tabs on the engine’s well-being.

Street cruisers were often retrofitted with late-model GM “605” power assisted steering, acquired from a salvage yard. This welcome convenience was rarely seen on all-out drag cars. Racers avoided anything that robbed precious HP.

The famous “Two Lane Blacktop” ’55 poses with movie cast members. L to R, Laurie Bird, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson (of The Beachboys). Scruffy, primered ’55 had a Tunnel-Ram 427 big-block built by Maryland’s Wheatley Brothers. The 1971 film and the ’55 have become popular classics.

Transmission choice has always been a question of personal preference. Manual options began with the classic three-speed, “three on the tree”. Next came the early Borg-Warner T-10, which was a ’57 model year option. The T-10 was followed by the Muncie M-20, 21 and M-22. B-W upped the ante in the early 70’s with the “Super T-10”, a stronger four-speed with gear ratios for drag racing.

Rob Vandergriff was another early Pro-Mod pioneer with this radical ’57. A 650 CID big-block and mega-doses of nitrous fueled sixes and 210 mph. Thunder Craft Boats and Danchuck, the popular California based 55-57 parts source were sponsors for this and Vandergriff’s next fast ’57.

The bar was raised again with the Doug Nash’s DNE Four-Plus-One. This five-speed offered almost limitless gear ratio options and easy maintenance through its clamshell style magnesium case. Its heavy-lug synchronizer teeth were engineered purely for wide-open-throttle, “power shifting”. Suddenly, every Modified Eliminator racer had to have a DNE five-speed. They were quicker, stronger and vastly more reliable than homemade “crash-box” modified boxes. Nash later released an equally popular street version a couple years later.

John Dianna ran a highly scienced, G/SA ’56 panel wagon during 60’s Golden Age of Junior Stock. Here at the NHRA ’68 Springnationals, Englishtown, NJ, Dianna used 225 hp 265 and micro-precise tuning. John became Editor and Publisher of Hot Rod Magazine, later founded Buckaroo Publishing.

Four or five-speed, these superior manual transmissions were easily installed in a Tri-Five. The five-speed required a shorter driveshaft, but these were available at shops eager to cash in on the popularity of the longer DNE units.

Hollywood, Florida engine builder Russ Barfield ran fast ‘55’s in B and C/Gas, and always with manual four-speed transmissions. Russ launches after flag start at Miami’s Masters Field. South Florida Timing Association’s famous bus carried timing system, PA and support gear for portable drag strip set-up.

Tri-Five automatic transmissions began with the stock, iron-case PowerGlide, or “Slip & Slide PowerGlide” as it was derisively known. ’57 Chevys had another option, the Turbo-Glide, but these were rare, and almost never used for racing. The iron-case PowerGlides were used only where Stock Class rules required them. An obscure option, the GM four-speed HydraMatic, was also available and some well- known Junior Stock racers used them successfully.

The late Paul Blevins’ classic ’55 Nomad wagon, here in Englishtown pits, earned a reputation as a Modified Elim killer in the 60’s. His skills helped his move into Pro-Stock upper-ranks with a SBC Vega, again very successfully.

The 1967 Turbo-Hydramatic TH-350, and later the TH-400 changed the face of drag racing, especially for Tri-Five Chevys. These high-strength, three-speed transmissions could be used with high stall-speed torque converters and manual shifting for greatly improved performance. The TH-350 was a favorite for a small-block, and the TH-400 had plenty of beef for even serious big-block engines. The trans-brake followed, and it too greatly impacted the 55-57 drag racing ranks.

Some days even a great day at the drags goes bad. Jimmy Waibel’s ’57 210 Sport Coupe stock ’57 axles were lacking in strength at 1968 NHRA WCS meet, Warner Robins, GA. Here Waibel stares-down the offending axle before repairing his ’57 210 Sport Coupe and running in Stock Eliminator next day.

Perhaps more surprising has been the emergence of the modern, aluminum case, hybrid PowerGlide for drag racing. The PG has risen to become the most popular automatic in drag racing today. Of course, all that remains of the original stock PG is the name itself. Today’s PowerGlide uses only a handful of factory PG parts. Modern ‘Glides have reinforced aftermarket aluminum cases, built-in safety bellhousings and super strong internal components. Gearing is available in varying ratios. Modern PG units regularly handle engines of 1,500+ hp, an amazing leap from the old “Slip & Slide”. Best of all, they are all 55-57 bolt-in’s.

Classic face off at Palm Beach Intl. Raceway, 1965, for C/Modified Prod. Near lane is Roger Vinci, from Orlando, far lane is Bill “Buzzard” Bussart. Buzzard and Dave Cochrane took C/MP class trophy home to Hialeah, Florida.

Atlanta’s Steve Hood and Ken Payne ran Div. 2 F/Gas during mid-1960’s. This Gatornationals pit scene is typical. Tow-bar was used by many racers of the era. In the background is ECDT Hall of Fame member Harold Dutton’s SS/B ’68 426 Hemi Barracuda. Dutton’s “Drag Hag” was also from Atlanta area.

Tri-Five exterior appearance was one area where self expression became an art form. In drag racing colorful car names were amazingly diverse. Tri-Five racers often took their nicknames along as they moved upwards. Popular expressions and movies became catchy car names. “Chevy A Go-Go”; “Good, Bad & Ugly”; “Monster Mash”; “007”; “USA-1”, “Yoo-Hoo-Too”, “Dr. No”; “Mad Medic”; “The Executioner”, “Stormin’ Bull”; “Bad News”, “Boss Chevy”, “Tokyo Rose”; “Poison Ivy”; “Shake, Rattle & Run” and “Godzilla” were just a few.

This magnificently flamed ’57 is a show stopper. House of Kolor paint and extreme detail make this Bel-Air a killer. Tri-Five Chevys have long been popular with customizers and for modern show car efforts.

Many Tri-Fives were raced sporting the same enamel paint scheme they left the assembly line with. Factory two-tone designs were attractive as well as popular, even when lots of racing decals and sponsor names graced their sides. For some, stock paint was replaced with elaborately done custom paint jobs. “MetalFlake”, a paint design that incorporated minutely ground flecks of metallic dust covered by a generous coat of clear lacquer was popular. Also popular were “Candy Apple” paints first offered by 50’s customizers. Candy Apple Red looked exactly like a freshly dipped, carnival candy apple.

Ratty, rusty, and primered, this ’55 four-door made the Hot Rod Power Tour. Looks are deceptive as front suspension got full rebuild. An aluminum radiator and likely V-8 power lurks behind that famous egg-crate grille.

The choice of Tri-Five rolling stock was equally diverse. Some used exotic, real magnesium alloy wheels from American Racing or Halibrand. Other choices were aluminum, five-slot wheels from ET and Mickey Thompson, five-spoke wheels from ET, or chromed steel Keystone Kustom or Cragar S/S. Like the 55-57 Chevy, Cragar S/S five-spoke wheel became a Tri-Five classic, and they remain popular today. High-end, aftermarket alloy wheels are available in a wide variety of styles. Weld, Centerline, and Monoque are just a few of the firms producing race quality wheels for Tri-Fives. Just as many low-buck rides of yesterday, and sometimes even today, retain the stock steel wheels, painted body-color, stylish red, or painted with a spray can of hardware store silver paint.

In spite of their 50+ year’s age, Tri-Five Chevys continue to remain a major part of the car hobby. During their three model-year reign Chevrolet built more than 4,800,000 Tri-Fives, insuring a ready supply of “donor cars and parts” for years to come. Those aftermarket firms specializing in Tri-Fives have stepped up in ways never before imagined. How astonishing is it that if your checkbook is up to the task, you can build a complete ’55 or ’57 Chevy using nothing but brand new, shiny fresh parts, from the ground up!

Nothing beats the sexy look of a ’57 Bel-Air Sport Coupe, bad-black and ready to light up those generously wide tires! This ’57 has slotted aluminum wheels, chrome headers, vintage decals and crowd-pleasing, resto-mod appearance.

1955, 56 and 57 Chevy’s truly were cultural icons of the decade. The mere mention of “The ‘50’s” easily brings to mind the finned image of a Tri-Five from a much simpler time. Whether it’s a rusty, dented and primered, street driven beater or 1,000 point Concourse beauty, the ever appealing lure of the Tri-Five Chevy has a life of its own. For drag racing, the 55-57 may be nostalgia in today’s computer numerically controlled, digital world, but they have managed to not only hold their own, but are more popular and in demand than ever before!

What could be better for those of us who grew up dreaming of one day owning our own Tri-Five for street, drag strip, or maybe both?

Author Note: Most of the images are from my personal collection. Some were obtained on the public domain of the Internet. All image creators are gratefully thanked for preserving these photos from long ago, and today.